Across California, the companies that are trying to build charging stations for electric trucks are being told that it will take years — or even up to a decade — for them to get the electricity they need. That’s because utilities are failing to build out the grid fast enough to meet that demand.

This poses a major problem for a state that’s aiming to clean up its trucking industry. California has the most aggressive set of truck electrification goals in the country, and compliance deadlines are coming up fast.

State legislators did pass two laws last year — SB 410 and AB 50 — ordering regulators to find ways to speed up the process of getting utility customers the grid power they need, and last week the California Public Utilities Commission issued a decision meant to set timeframes for this work.

But charging companies, electric truck manufacturers, and environmental advocates are not happy with the result. They say the decision does next to nothing to get utilities to move faster or work harder to serve the massive charging hubs being planned across the state.

“It’s shocking how little the commission did here. They basically adopted status quo timelines across the board,” said Sky Stanfield, an attorney working with the Interstate Renewable Energy Council, a nonprofit clean energy advocacy group.

California’s struggle to deal with this issue is raising doubts about not only whether the state can meet its own climate goals but also whether truck electrification targets are achievable at all. States in the U.S. Northeast and Pacific Northwest with transportation-electrification targets will also need to build megawatt-scale charging along highways. Those projects will likewise require grid capacity upgrades that take a much longer time to plan and build than charging sites for passenger vehicles.

Stanfield and IREC believe that the CPUC’s decision both is inadequate and runs counter to clear instruction from California law. SB 410 orders the CPUC to craft regulations that “improve the speed at which energization and service upgrades are performed” and push the state’s big utilities to upgrade their grids “in time to achieve the state’s decarbonization goals.”

But the state’s electric truck targets simply won’t be met if charging stations aren’t built more rapidly, Stanfield said. “No one’s going to buy a fancy EV truck that costs well over $100,000 if they can’t charge it.”

IREC isn’t alone in this perspective. Powering America’s Commercial Transportation, a consortium of major EV charging and manufacturing companies, wrote in its comments to the CPUC that the decision “does not comply with either the requirements or legislative intent” of the law.

PACT asked the CPUC to set a two-year maximum timeline for utilities to build new substations and complete the more complex grid upgrades required by large EV charging depots.

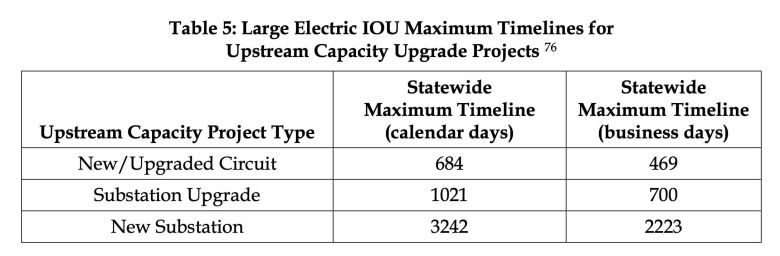

But instead, the CPUC simply had Pacific Gas and Electric, Southern California Edison , and San Diego Gas & Electric report how long these major “upstream capacity” grid projects are taking today and then used the lower average of that historical data to set maximum timelines that utilities should meet in the future.

Those timelines are much, much too long, electric truck manufacturers, charging-project developers, and clean transportation advocates say. They stretch from nearly two years for upgrading distribution circuits and nearly three years for upgrading substations to nearly nine years for building the new substations that utilities say they’ll need to power truck-charging depots currently being built.

“We’ve put in millions of dollars in the facilities we’ve already upgraded, and more that are in motion,” said Paul Rosa, a PACT board member.

As senior vice president of procurement and fleet planning at truck leasing company Penske, he is responsible for the company’s transport projects, including truck-charging projects in Southern and Central California.

But those projects represent just a fraction of the 114,500 chargers required to support the 157,000 medium- and heavy-duty vehicles that the California Energy Commission forecasts the state will need by 2030.

“If we can’t get the power, this all comes to a screeching halt,” Rosa said.

The big problem with the grid and trucks

The slow and burdensome process of getting new customers connected to the grid — “energization” in CPUC parlance — isn’t a problem for just EV trucks.

PG&E has been under fire for years for failing to deliver timely grid hookups to everyday commercial and residential projects — a result, critics say, of poor planning and resource management.

The CPUC’s new decision does set a 125-business-day maximum timeline for these less complicated energizations. If those targets are met by utilities, “maximum timelines for grid connections could be reduced up to 49 percent compared to current operations,” the CPUC noted in a fact sheet accompanying the decision.

“I think the commission got it right” on these less complicated energization targets, said Tom Ashley, vice president of government and utility relations at Voltera, a company building EV charging projects across the state.

But how the commission handled the larger-scale grid upgrades — the kind needed to get EV truck-charging stations up and running — is a different story, he said. “That is where the industry is really frustrated that we didn’t get the help, and the utilities didn’t get the direction.”

The state’s Advanced Clean Trucks rule requires truck manufacturers to hit minimum targets for zero-emissions trucks as a percentage of total sales over the coming years, ratcheting from 30% of all medium- and heavy-duty vehicles by 2028 to 50% by 2030.

And California’s Advanced Clean Fleets rule requires the state’s biggest trucking and freight companies to convert hundreds of thousands of diesel trucks to zero-emissions models over the next 12 years, with earlier targets for certain classes of vehicles, including the heavy trucks carrying cargo containers from California’s busy and polluted ports.

Right now, many of the plans to build charging hubs for those trucks are stuck in grid-upgrade limbo — and the CPUC decision offers little indication it will get them unstuck.

“We’ve submitted for well over 50 projects in the past two years, looking for the right property to acquire,” said Jason Berry, director of energy and utilities at Terawatt Infrastructure. The startup has more than $1 billion in equity and project finance lined up to build large-scale charging hubs, including a network that will stretch from California to Texas along the I-10 highway, a major trucking corridor.

But of the sites Terawatt has scouted in California, “about 95% of those do not have the power we’re trying to request,” Berry said. To serve proposed charging hubs in California’s Inland Empire, utility SCE has said that it will need to expand existing substations, which takes four to five years, or build a new substation, which takes at least eight years, Terawatt said in May comments to the CPUC.

Terawatt is far from the only company facing delays. In testimony to the CPUC, Berry pointed out that Tesla has told the agency that 12 Supercharger sites with 522 charging stalls are facing delays because of capacity issues in SCE territory. A state-funded electric truck-charging project in the Inland Empire is also held up due to similar constraints.

The main problem is that large-scale charging sites can be built much faster than utilities are used to moving, Berry said. “We’re building projects, maybe ideally starting at 10 megawatts and then going to 20 megawatts,” Berry said. That’s about the same load on the grid as would be caused by an entirely new residential neighborhood or big commercial or industrial site.

But while those sites typically take years to plan and build, a new truck-charging site can go from planning to completion in less than a year.

“They have to have a mechanism to start on those things, or every single project is going to be four to five years out — which is what we’re being told on so many of these today,” he said.

The same point was made by Diego Quevedo, utilities lead and senior charging-infrastructure engineer at Daimler Truck North America, which joined fellow electric truck manufacturers Volvo Group North America and Navistar to weigh in on the CPUC proceeding.

“Trucks can be manufactured by OEMs and delivered approximately six months after receiving an order,” Quevedo said in testimony before the CPUC. But fleets won’t order trucks if they lack the confidence the utility grid infrastructure will be built and energized when the trucks are delivered.”

Utilities’ grid-capacity additions are taking from seven to 10 years to “plan, design, budget, construct, and energize,” he said. Unless those capacity expansions can be sped up significantly, “electric trucks become expensive stranded assets that are unable to charge,” he said.

Why it’s so hard to speed up expensive grid upgrades

California’s major utilities have a different perspective. They’ve argued in comments to the CPUC that it may be difficult or impossible to move more quickly on such complicated work.

First, as utilities have pointed out, many of the things that can slow down major grid projects are beyond their control. In a filing with the CPUC, PG&E noted that “one capacity upgrade project may face an extended timeline due to lengthy environmental assessments and permitting processes, and another may encounter challenges in acquiring materials in a timely manner due to manufacturer issues.”

IREC’s Stanfield conceded that equipment backlogs and environmental and permitting reviews are barriers to moving more quickly. “But we have to make it go faster if we want to hit our climate goals, if we want manufacturers to build clean trucks.”

And there’s an even bigger challenge to making major changes to the grid in anticipation of booming demand from EV charging: the cost involved.

“Lack of funding is the big block to meet the anticipated load growth,” Terawatt’s Berry said.

California’s utilities are already spending more than they ever have on their power grids, for myriad reasons. They are passing the costs of grid-hardening investments and integrating new clean energy into the power system on to customers in the form of electricity rates that are now the highest in the continental U.S.

Electricity rate increases are an economic and political crisis in California. Keeping them from rising any further has become the chief focus of lawmakers and regulators in the past several years. Any proposals that could raise customer bills even more face a tough battle — including plans to build grid infrastructure for electric truck-charging hubs.

SB 410 does give the CPUC permission to allow utilities to increase their spending in order to meet tighter EV-charger energization timelines. But the bill also calls on regulators to subject these requests to“extremely strict accounting.”

PG&E was the first utility to submit a ratemaking mechanism under SB 410 earlier this year. The Utility Reform Network, a ratepayer advocacy group, quickly filed comments protesting the utility’s plan to create a “balancing account” that would enable it to recover as much as $4 billion in additional energization-related spending from customers — a structure that falls outside the standard three-year “rate case” process for California utilities.

“PG&E’s electric rates and bills are now so high that they threaten both access to the essential energy services that PG&E provides and the achievement of the state’s decarbonization goals, which rely in part on customers choosing to electrify buildings and vehicles,” TURN wrote in its comments.

TURN wants the CPUC to limit the scope of SB 410’s extra cost-recovery provisions to “specific work needed to complete an individual customer connection request,” rather than the kind of proactive upstream grid investments that truck-charging advocates are calling for. TURN would prefer that those projects remain part of general rate cases, the sprawling proceedings that determine how much utilities spend on their grids.

But those general rate cases can take up to five years to move from identifying the broader, systemwide analyses of how much electricity demand is set to rise to winning regulatory approval in order to build the expensive grid infrastructure needed to actually meet those growing needs. That’s too long to wait to fix the problem, charging advocates say.

At the same time, ratepayer advocates are challenging utility efforts to expand the scope of their larger-scale plans to meet looming EV charging needs. In SCE’s current general rate case, TURN and the CPUC’s Public Advocates Office, which is tasked with protecting consumers, are protesting that the utility is overestimating how much money it needs to spend to prepare its grid from growing EV-charging needs.

Terawatt and other charging developers and electric truck manufacturers argue just the opposite — that the utility isn’t planning to spend enough over the next three years. In his testimony in the rate case, Terawatt’s Berry complained that TURN and PAO are challenging utility and state forecasts of future charging needs based on outdated data, and that failing to approve the utility’s funding request will “ensure that California fails to achieve its zero-emission vehicle goals.”

Charging advocates have also asked the CPUC to create a separate regulatory process to consider the grid buildout needs spurred by large-scale charging projects. But the CPUC rejected that concept in its decision last week, stating that “preferential treatment based on project type is prohibited by California law.”

Finding a way to plan the grid ahead of big charging needs

All these conflicting imperatives leave the CPUC with tough choices to resolve the gap between charging needs and grid buildout plans, said Cole Jermyn, an attorney at the Environmental Defense Fund.

The CPUC “can and should do more here. I don’t think the timelines they set here are as strong as they could have been,” Jermyn said.

At the same time, “the commission had an incredibly difficult job here. The targets are not easy to set, and they had a very short timeline to do it.”

That’s why multiple groups have asked the CPUC to focus its next phase of work on implementing SB 410 and AB 50 on a key issue: aligning grid planning and EV charging needs.

“Part of the work here is figuring out what that proactive planning looks like,” Jermyn said. “The utility cannot wait around for customers to come to them and say, ‘We need 5 megawatts of capacity.’ They need to be looking out into the future to start proactively preparing their distribution grids for all this electrification.”

At the same time, “how do you balance that need for proactive planning and investment with ratepayer investments along the way to make sure this isn’t building assets that won’t be used and end up on someone’s bills?” Jermyn asked. That will be complicated, but, he added, “I think it’s doable — especially for a state that has such clear goals.”

SB 410 also specifically called on the CPUC to take California’s decarbonization goals into account in tackling energization delays — but last week’s decision “was relatively silent on that issue,” Jermyn said.

“This is something we think is incredibly important to be in the next phase of this proceeding, because it wasn’t in this one,” he said. “We don’t know if the timelines they set are meeting that goal or not. We should figure out if they are.”

EDF has advocated for years for utilities and regulators to approve grid spending in advance of EV charging needs, noting that such spending will end up reducing costs for utility customers in the long run.

That’s because California’s utilities don’t earn profits directly through electricity sales. Instead, their rates are structured to repay their costs of doing business. More customers buying more electricity can spread out the costs of collecting the money that utilities need to operate and invest in infrastructure, which can reduce the rates per kilowatt-hour that utilities must collect in future years.

This isn’t just a California issue. Nearly a dozen states — including Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington — have adopted advanced clean truck rules. They’re not as aggressive as California’s rules, but meeting them will still require grappling with the same challenges around proactive grid planning.

Voltera’s Ashley worried that the CPUC’s decision may set a bad precedent for other state regulators on this front. “The commission has a really hard job. They’re tasked with a lot of complicated policy and execution,” he said. “And at the end of the day, they have some overarching mandates, including affordability for ratepayers,” that complicate the task.

But California also has “the most aggressive targets, goals, and statutory requirements around not just electrification of transportation but electrification of other segments” of the economy, he said. “If California doesn’t get this right, who will?”