California policymakers are searching for ways to rein in the cost of expanding the state’s power grid, which is necessary to combat climate change. Experts warn they’re missing an opportunity that’s right in front of them — taking advantage of the growing number of clean energy technologies owned by utility customers.

California ended its legislative session last month unable to pass a proposed legislative package to address rising electricity rates for customers of Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric, which serve about three-quarters of the state’s residents.

Lawmakers also failed to pass several bills aimed at boosting the role battery-backed rooftop solar systems, electric vehicles, and electric heat pumps and water heaters can play in balancing the power that’s available on the grid.

Replacing fossil-fueled vehicles with EVs, and gas heating systems with heat pumps, will increase statewide electricity demand, requiring utilities to invest billions of dollars to upgrade their grids. But those same technologies can shift when they use power to avoid the handful of hours per year when demand spikes. That’s important, because the cost of building power grids is largely determined by the size of those spikes — and in turn is a core driver of California’s energy affordability crisis.

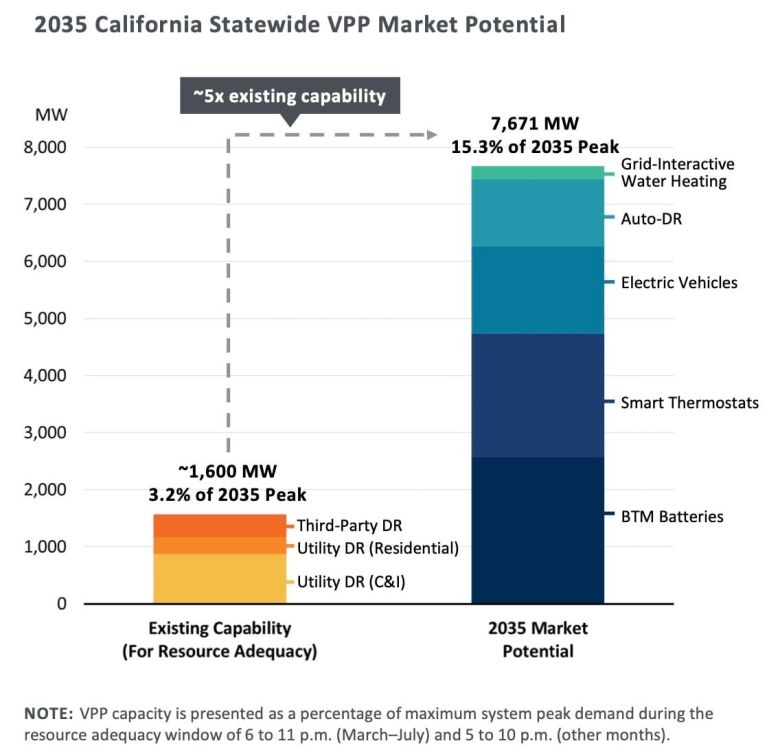

If the state can use distributed energy resources to shave a bit of demand from grid peaks, it stands to save big. One example: In an April report, consultancy Brattle Group projected that virtual power plants, which can shift when EVs and electric appliances draw from the grid or tap into customer solar and battery systems, could provide more than 15 percent of the state’s peak grid demand by 2035. That would amount to around $550 million per year in consumer savings.

About $500 million of that would flow directly to the customers who own the devices, which could help defray the cost of buying EVs and heat pumps, two technologies that need to be rapidly adopted to meet climate goals. But because tapping into those devices would cost less than making large-scale investments, utilities — and by extension all of their customers — would save about $50 million per year by 2035, Brattle found.

“California’s affordability challenges are years in the making and are worsened by climate-driven impacts like heat waves and wildfires,” said Edson Perez, who leads trade group Advanced Energy United’s legislative and political engagement in California. “However, there are critical steps we can take now: optimizing our existing grid, maximizing the cost-effectiveness of essential grid upgrades, and fully leveraging available technologies like distributed energy resources.”

But as it stands, California isn’t putting the full weight of policy support behind these types of distributed energy programs.

Pilot programs have petered out, seen their budgets clawed back, or have been outright canceled. The scale of demand-side resources operating in the state has actually declined over the past decade, even as the state’s grid stresses have increased. And efforts to create statewide targets for distributed energy — like those that helped spur California’s rooftop-solar and home-battery leadership — have failed to gain traction, including a proposed bill in the state’s just-concluded legislative session.

Advocates say it’s time for the state to change that — especially since there’s an expiration date for capturing the value of DERs. Without policies to encourage utilities and customers to work together to realize the grid benefits of these technologies, utilities will simply build expensive, centralized infrastructure to meet rising electricity demand. Once that money is spent, potential savings can’t be realized, undermining the economic case for VPPs.

Unfortunately, utilities have clear incentives to discount the potential of VPPs as a money-saving tool, because they earn guaranteed rates of profit on capital investments like grid buildouts, but don’t for alternatives like VPPs. Plus, they’re held responsible for failing to keep pace with growing power demand — and are loath to rely on decentralized assets owned by customers in place of tried-and-true grid investments.

California’s VPP policy landscape

This utility reluctance may well explain why a roster of bills aimed at enlisting DERs to combat rising grid costs stalled in this year’s regular legislative session.

SB 1305 proposed requiring the California Public Utilities Commission to determine targets for utilities to “procure generation from cost-effective virtual power plants,” and then mandate that the utilities meet them.

Similar targets for rooftop solar and batteries have been valuable for boosting early-stage deployments in California, said Cliff Staton, head of government affairs and community relations at Renew Home, the company formed by the merger of Google Nest’s smart-thermostat energy-shifting service Nest Renew and California-based residential demand-response aggregator Ohmconnect.

“If you set the targets, you begin to provide the certainty to the industry that if you invest, there will be a return for your investment over time,” Staton said.

An early version of SB 1305 set hard percentage targets for VPP procurements by 2028 and by 2035. Those percentages were stripped from the bill later in the session, leaving the final targets up to CPUC discretion. The bill failed to clear a key legislative committee anyway.

Another bill that died in committee, AB 2891, would have expanded options for VPPs to capture the value of the peak load reductions they can provide. The legislation would have ordered the California Energy Commission to create methods for VPPs to reduce how much generation capacity each utility in the state must secure to meet peak grid demands in future years.

Only a handful of California’s community choice aggregators — the public entities that supply power to an increasing number of customers of the state’s major utilities — are using this approach today. But those CCAs have been able to start paying customers with solar and batteries for the value they can provide by reducing reliance on increasingly expensive contracts with centralized grid resources — mostly fossil-gas-fired power plants.

For more than a decade, state laws have called on the CPUC to create programs that reward customers for the energy and grid values provided by their solar panels, backup batteries, electric vehicles, and remote-controllable devices like smart thermostats and water heaters.

But these efforts have been plagued by an on-again, off-again approach from regulators and utilities. The California Energy Commission set a goal in 2023 of achieving 7 gigawatts of load flexibility from VPPs and other customer-owned resources by 2030; two of the CEC’s key contributions to that effort saw their budgets slashed this year.

Meanwhile, many of the programs launched by the CPUC over the past decade have stalled out due to overly complicated structures, or had their budgets reduced or canceled due to concerns over their cost-effectiveness.

The CPUC and the California Independent System Operator (CAISO), the entity responsible for managing California’s transmission grid and energy markets, argue that these programs have failed to perform as promised. Relying on them more would run the risk of eroding rather than improving grid reliability, they say.

But the companies engaging in these VPP programs — smart-thermostat providers like Renew Home and ecobee; solar and battery installers like sonnen, Sunrun, Sunnova, and Tesla; and demand-response providers like AutoGrid, CPower, Enel X, and Voltus — argue that overly complex and restrictive rules and compensation structures are to blame.

Adding to these challenges for would-be VPP providers is the declining value of rooftop solar. Major changes in California’s net-metering policies over the past two years have slashed the value of customer-owned solar systems, slowing the growth of the state’s leading rooftop solar market.

That’s a problem for VPP providers and advocates who see rooftop solar as an important way to help meet demand from households and businesses with EVs and heat pumps — and to charge up batteries with clean electricity that VPP programs can tap into later.

A host of bills were proposed to reset state policy to restore more value to customer-owned solar during this year’s legislative session. But only one — SB 1374, which restores compensation for schools that install solar — made it through.

California’s new rooftop solar regime does reward customers for adding batteries to store surplus solar power during the day and discharge it in evenings, when the grid faces its greatest and most costly stresses.

But solar and battery advocacy groups argue that those rewards haven’t counterbalanced the broader erosion of rooftop solar values — and that the VPP opportunities that have emerged in the state can’t yet be trusted to make up the remaining difference.

“It’s important for customers to find value in the investment they’ve made, and to help the grid and lower cost for all consumers,” said Meghan Nutting, executive vice president of government and regulatory affairs at Sunnova. “One of the problems with VPP programs so far is that it’s really tough to talk about that value proposition up front because programs are so short, you can’t count on them, or the funding isn’t there.”

Why grid costs and VPPs are intertwined

At the same time, California policies that encourage people to buy other distributed energy resources — namely EVs and heat pumps — are under threat from rising electricity rates, which are eroding the benefits of switching from fossil fuels.

A controversial policy enacted this year to reduce the per-kilowatt-hour rates paid by customers of the state’s big three utilities in exchange for higher fixed costs may or may not ease that pressure. But both opponents and supporters of the policy agree that shifting the balance of fixed and variable electricity costs does little to address the underlying problems.

Programs that enlist those exact same distributed energy resources to ease grid stresses have a much clearer value proposition, on the other hand.

About half of the electricity bills of customers of California’s three big utilities is made up of fixed costs like grid investments. A majority of those investments are tied to building a grid robust enough to supply power not just for average needs, but during the few hours per year when electricity use peaks.

Those peaks are getting bigger as California’s climate goals encourage more EVs and heat pumps to come online, and the costs of dealing with that have only just begun to be built into utilities’ broader grid investment plans. A series of studies ordered by the CPUC found that adding demand from EVs and heat pumps to the grid could increase ratepayer costs by more than $50 billion by 2035 — or, depending on the approach taken, costs could be contained to less than half of that over the same timespan.

One key variable in those distinct cost forecasts is whether EVs can be programmed or incentivized to avoid charging all at once and overwhelming the grid. “Smart charging” programs that encourage EV owners to shift when they charge their cars could save California ratepayers tens of billions of dollars over the coming decade.

With the right policies and technologies in place, big new grid demands like EVs could actually become valuable resources for energy in their own right. SB 59, a bill that passed in this year’s legislative session after failing to make it last year, orders state agencies to study the proper role for regulation that could require automakers to enable their EVs to support “vehicle-to-grid” charging — sending power from EV batteries back to homes, buildings, or the grid at large.

The challenge for utilities and regulators is finding the right mix of approaches that can allow them to take advantage of EVs, heat pumps, residential solar and batteries, and other distributed resources such that they avoid either overbuilding or underbuilding the grid, said Merrian Borgeson, policy director for California climate and energy at the environmental nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council.

“We have to be really careful with any new investment — but we do need to make new investments,” she said. “If we pull back too far on energizing loads like electric homes or EV trucks, we miss out on getting those loads connected.”